03.06.2020 – 16.01.2022

03.06.2020 – 16.01.2022

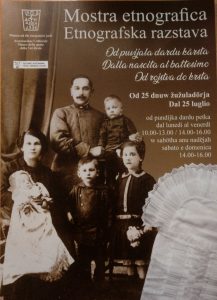

Od puvijala dardu karsta / Dalla nascita al battesimo / Od rojstva do krsta / From birth to baptism

FIRST ROOM

Engagement and marriage

The engagement was only the final stage of a „ceremonial“ which still had to be followed. In fact, before the engagement, even here in Resia, especially for young males there was the custom, first in groups then individually, to court the young women, for an undetermined period, by visiting them in their respective houses, in Resian tet w väs.

The promise of eternal love took place during the engagement. Often, in this condition, the boy gave the girl some small jewel (rings, earrings or necklaces) but not the wedding ring and, at times, they exchanged their own photographs. During this period, in which eternal love was promised, it could happen that the young man went away for long periods, due to work obligations or wars.

The wedding crowned the time of the engagement during which the woman, in the Resia Valley, as a maiden wore a particular style of the traditional dress and until the early 20th century used some elements with flashy colours. From the wedding and throughout her life she would dress mainly dark clothes except the socks which were, instead, white in colour.

About birth (pregnancy and parturition according to nature)

Understanding that you are pregnant from conception, as there was no other objective way, was once impossible. The women had the certainty of being pregnant only when they felt the baby moving in their womb around the fifth month and carried on the pregnancy working with the same rhythms, but taking care of themselves, as far as possible, until the moment of childbirth.

Birth began with labour. The adult women of the house or some relatives went into action by heating the water and preparing the various pieces of cloth necessary to wash the newly born child and the mother. Even in the Resia Valley, as indeed in many other places in Friuli and beyond, until the early 70s of the 20th century, if there were no other particular conditions, almost all children were born at home.

SECOND ROOM

Women things: midwives, social links and solidarity

Midwives were called in this way from the 18th century, because they were able to „lift“ the infant from the body of the pregnant woman. In Resian, on the other hand, they are called te žane ka wzdigüwajo which means „women who gather“, or gronkomori – from the Friulian grand(d) comari. These women were able to intervene in the most disparate circumstances of the difficult moment of the birth of a new life. For their services, they did not ask for anything in return even if the families themselves repaid them with money or with some consumer goods of their own production, for example, cheese or firewood.

Other wise women, who may not have been midwives, were called instead when the child cried continuously and insistently because it was thought he had been „infected“ by people, not family members, with „evil“ powers. These knew a „ritual“ that was performed to calm the baby and make him or her stop crying. The ritual was told to us in these words:

The feast on the occasion of the baptism, which took place after the happy event, where the family ate and drank something together, was called in Resian Karstïne, Kristïne. Also on that occasion, as in other large parties or for long journeys, the sope were prepared (slices of stale bread soaked in beaten eggs, fried in oil and sprinkled with sugar) that everyone ate, including the new mother. It could also have been the midwife herself to prepare this dish. From this fact, especially when someone wanted to let people know that a woman was pregnant, originated the saying Ćemo mët sope which means „Soon we will eat sope„.

THIRD ROOM

The sacrament of Baptism and the education of children

The baptismal ark for the transport of the newborn to church was used by those, who lived closest to the church with the baptismal font. This ark, by those who lived farther away, was replaced by a pannier, sometimes made with a particular shape designed to protect the baby from the weather and thus provide for his salvation in every way.

The baptism celebrated in church had to take place within twenty-four hours from birth because people feared for the survival of the baby. It was the godparents and godmothers, who took him or her to church, wrapped in an embroidered white baby carrier called plahütica in Resian. The same people, often, also chose the name of the newborn baby, sometimes without the knowledge of the mother, who had indicated a different name..

The children belonged to everyone and grew up without much trouble. There were no health-threatening games, you were happy to live with what you had and you played with little. In the courtyards and on the streets, the children, who often lived in conditions of extreme poverty, belonged not only to their parents, but to the whole community to which their supervision and education were entrusted by custom. Even in these situations, the transmission of local culture and traditions took place with its myths, fairy tales and legends, which also marked their education.

The purification of the new mother ended the period following the birth of a child. Forty days after childbirth, the mother who was wearing a white headdress and sheet, which served to cover her in full, was accompanied by some family member or by the midwife on the threshold of the church. There, kneeling, she waited for the priest to perform the ritual of atonement for her.

FOURTH ROOM

Fairy tales and scholars

The popular stories related to the various topics studied in this ethnographic exhibition and published in the catalogue are taken from the rich narrative heritage of the local oral tradition, which the people of Resia have handed down to today. These also help us to better understand the various local aspects related to birth, baptism and everything that happened in these situations.

The scholar, who was most interested in the oral narrative heritage of Resia, was the Slovenian academic folklorist Milko Matičetov (1919-2014), one of the leading European experts in the field. From the 60s of the 20th century he collected hundreds of fairy tales, stories, legends and mythological tales. One of his most significant narrators was Tïna Wajtawa, Valentina Pielich (1900-1984) of Stolvizza, who told him several hundred stories.

14.10.2017 – 14.03.2020

Zverinice tu-w Reziji. Die ethnografische Ausstellung ueber Maerchen des Resia Tales wurde im Oktober 2017 ausgestellt und dauerte bis Februar 2020.

2014

Il recupero degli arredi tradizionali: il banco dotale/bank

2012

Gli arrotini della Val Resia – Ti rozajanski brüsarji

Die ethnografische Ausstellung wurde im Februar und im März 2012 in der Villa Manin ausgestellt. Es gibt auch ein Katalog der Ausstellung.

2010

2010

Škula anu školeriji tu-w Reziji (Schule und Schüler in Resia)

Diese Ausstellung wurde im August 2010 im Kulturzentrum “Rozajanska Kulturska hisa” in Resia und vom 2. April bis 31. Mai im Venezianischen Palast in Malborghetto veranstaltet.

1999

1999

Le fornaci della Val Resia (Brennöfen im Resiatal)

Diese Ausstellung wurde in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Kulturverein “Rozajanski Dum” im August organisiert. Es wurden Fotos mit Erläuterungen der Reste der Brennöfen des Resiatals ausgestellt.

Zu pädagogischen Zwecken wurde auch ein Brennofen in Originalgröße gebaut.

1998

1998

La tessitura in Val Resia (Weben in Resiatal)

Diese Ausstellung von Stoffen und Bekleidungen dieses Tales wurde im August organisiert.